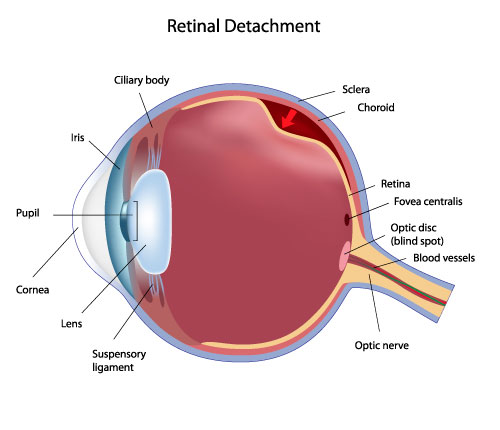

Retinal detachment occurs when the transparent layer of the retina separates from the pigment layer. As the cones and rods contained in the transparent layer are lifted away, vision becomes darkened and distorted. Complete detachment leads to complete loss of vision.

Retina Detachment

The middle of our eye is filled with a clear gel called vitreous that is attached to the retina. Sometimes tiny clumps of gel or cells inside the vitreous will cast shadows on the retina, and you may sometimes see small dots, specks, strings or clouds moving in your field of vision. These are called floaters. You can often see them when looking at a plain, light background, like a blank wall or blue sky.

As we get older, the vitreous may shrink and pull on the retina. When this happens, you may notice what looks like flashing lights, lightning streaks or the sensation of seeing “stars.” These are called flashes. Usually, the vitreous moves away from the retina without causing problems. But sometimes the vitreous pulls hard enough to tear the retina in one or more places. Fluid may pass through a retinal tear, lifting the retina off the back of the eye — much as wallpaper can peel off a wall. When the retina is pulled away from the back of the eye like this, it is called a retinal detachment.

The retina does not work when it is detached and vision becomes blurry. A retinal detachment is a very serious problem that almost always causes blindness unless it is treated with retinal detachment surgery. If you have retina related problems with your vision and would like a second opinion please feel free to speak with one of our doctors. Our retina eye medical staff will arrange an appointment for a complete diagnosis.

Retinal Reattachment Surgery

Some retinal detachments can be treated with laser therapy in the clinic if they are small. Many factors determine which need to be treated. Three types of eye surgery are done for retinal detachments: scleral buckling, pneumatic retinopexy, and vitrectomy with either local or general anesthesia.

During a pneumatic retinopexy, the surgeon injects a gas bubble directly inside the vitreous cavity of the eye to push the detached retina against the outer wall of the eye (sclera). The gas bubble initially expands and then disappears over 2 to 6 weeks. Proper positioning of the head afterward is critical for the success of the procedure. The break in the retina is either sealed with laser or freezing before or after the injection of the gas bubble. The success rate of this procedure can be as high as 80% and does not change the outcomes if further surgery is needed.

Vitrectomy surgery is the most common method of reattaching retinas today. It is performed in the hospital under general or local anesthesia. Small trocars are placed through the sclera to allow access to the retinal detachment. A fiber-optic light, a cutting source (vitrector), and a fluid infusion are placed in these trocars to perform the operation. The vitreous gel of the eye is removed and replaced with a gas to refill the eye and reposition the retina. A scleral buckle is sometimes also performed with the vitrectomy. The gas eventually is absorbed and is replaced by the eye’s own natural fluid. In more complicated cases, silicone oil may be placed in the vitreous cavity instead of a gas. This oil may be removed at a later date.

A scleral buckle, which is made of silicone, plastic, or sponge, is placed around the outer wall of the eye. The buckle is like a belt around the eye that can be adjusted during surgery. This application compresses the eye so that the hole or tear in the retina is pushed against the outer scleral wall of the eye, which has been indented by the buckle. The buckle may be left in place permanently. It usually is not visible because it is covered by the conjunctiva (the clear outer covering of the eye), which is carefully sewn (sutured) over it. Compressing the eye with the buckle also reduces any possible later pulling (traction) by the vitreous on the retina. Retinal reattachment rates run around 80% for the first surgery and around 90% with multiple surgeries. Some retinal detachments cannot be fixed.

Retinal Vein Occlusion

Veins in your eye (known as retinal veins) are an important part of your eye’s normal circulation. They move blood out of your eye toward your heart. A retinal vein occlusion (RVO) is the blockage of one of these veins. RVO can lead to swelling of the macula, the part of your eye responsible for central vision and fine detail. This swelling can cause blurry or distorted vision in the affected eye. In some cases, RVO can lead to permanent vision loss.

RVO is a disease of the retina that affects approximately 180,000 people each year in the U.S.

What are the symptoms?

Some of the symptoms you may experience with retinal vein occlusion include:

- Blurry Vision

- Distorted Vision

Some people with RVO may not notice any symptoms. In fact, some cases are detected through a routine eye exam. So it’s important to have your eyes checked regularly. While anyone can get a retinal vein occlusion, it tends to happen to people who are over 50 years old.

People with certain medical conditions have an increased risk of RVO. These conditions include:

- Diabetes

- Hardening of the arteries

- Glaucoma

- High blood pressure

Other factors that may contribute to RVO include:

- Smoking

- Obesity

- Oral contraceptives

How will my RVO be diagnosed?

Eye exams can often detect RVO. Dr. Thomas may use a fluorescein angiography to evaluate your blood flow. Computer imaging can also capture detailed cross-sectional images of your retina. These images are referred to as OCT scans. They are used to detect and measure fluid build-up (macular edema) and monitor the disease. Other tests we may perform include visual field tests that check your peripheral vision.

What should I expect from treatment?

While there is no cure for RVO, there are ways your Retina Specialist may treat your condition. Treatment for RVO may require multiple intraocular injections to maintain vision and regular follow-up examinations over time.